– (Filmgrab, 2021)

There is pleasure in the pathless woods,

– lord byron

There is rapture on the lonely shore,

There is society where none intrudes,

By the deep sea and music in its roar,

I love not Man the less, but Nature more…

Sean Penn’s “Into the Wild”, based on Jon Krakauer’s book about the life of Christopher McCandless, begins with this poem. The words echo throughout the two hour long visually stunning journey of Chris from College graduate to lonely nomad, huddled inside an old Fairbanks City bus. It describes the pleasure found in nature, away from human intrusions and structures, away from capitalist habits and responsibility and taxes.

The film’s cinematography communicates these pleasures and evokes empathy from audiences seeking escape from societal power structures, namely capitalism and neocolonialism. I’ll detail why film is a valuable medium through which to communicate complex geographical ideas as more than just space and place (Driver, 2003), to make academia more accessible and to move away from purely objective study. I will also detail why visual art and valuing the subjective is important to the future of geography and why “Into the Wild” provides a potent example of these values to a wider audience, encouraging inclusivity, understanding and rejection of the establishment.

Visualising Alienation

Alienation permeates the film, from Chris’ disgust with 1990s American overconsumption to the inward alienation he feels discovering his father’s infidelity, which fosters a deep sense of betrayal. This leads him to create his alter ego, Alexander SuperTramp, a hero who isn’t afraid to wander as far as he can in search of true happiness: from the Mexico Border to Alaska.

The overconsumption, however, is best seen in Chris’s jarring passage through Los Angeles, where Penn’s direction assaults the senses:

“There is steady HONKING of CAR HORNS, WAILING of POLICE SIRENS, AMBIENT HOSTILE BANTER, GRINDING ENGINES OF BUSES, puffs of diesel exhaust choke us.”

Katz’s (2002) theory of ‘vagabond capitalism’ is depicted in the city’s dereliction and the overcrowded, overstimulating homeless shelter where Chris flees, onto the next train heading north. Despite Chris’s desire to live off-grid, he repeatedly runs into the need for documentation, money, and work; the grip of an “unsettled” and “materialist” (Katz, 2002, 709) capitalism mirrors the vagabond status of Chris himself. This reinforces the spatial and internal alienation within Chris, driving him further and further away from societal contact.

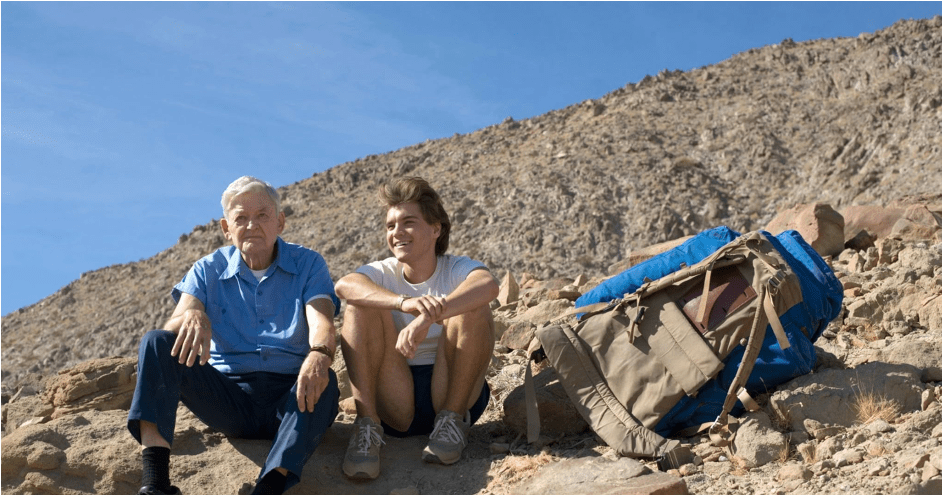

Penn’s direction does, however, critique this kind of wandering capitalism and its persistence even in Alexander SuperTramp’s life by highlighting the beauty of human connection in the people Chris meets along his journey across the US; specifically, other nomads, foreigners, and dreamers who share his desire to explore the world. The vivid expressions of natural beauty that Chris encounters are enhanced by these people: swimming with Jan and Rainey or contemplating life’s purpose with Ron.

(IMDB, 2007a)

(IMDB, 2007c)

These subjective, emotional encounters throughout the film critique the spatial nature of capitalism, instead highlighting the enduring presence of joy, togetherness, healing and emotional resonance. Traditional geographic study prioritises objectivity “to expand its competitive value and leverage” (Oyenuga et al., 2019, 39), much like the persistent nature of capitalism to incentivise progress, “Into the Wild” critiques structures of oppressive everyday life by highlighting the beauty around us, in the oceans and trees but most importantly in the people we meet. The space within the film becomes shaped by Chris’ experiences and therefore socially produced, reflecting a new geography that finds true value in the lived experiences of ordinary people (Santos, 2021).

Challenging Neocolonial Gazes and Deconstructing “the Wild”

Aligning with this ‘new’ geography, the film both supports and critiques neocolonial narratives surrounding ‘The Wild’. At first glance, ‘The Wild’ is visualised in the cinematography of the great landscapes Chris encounters as he travels to the Alaskan ‘wilderness’ – a place devoid of humans. His yearning to be “all the way out there” aligns with nature as a space of unbounded freedom; however, his naïve preconceptions about surviving alone in this isolated beauty quickly unravel.

(IMDB, 2007b)

Deconstructing ‘The Wild’ as “human free” (Rogers, 2012, 23) and a place of escape from the clutches of capitalist greed and consumerist materiality, becomes the film’s focus as Chris ventures in search of personal growth and identity. The neocolonial wilderness is expressed in the solitude and the subsequent happiness he feels at escaping the perceived constraints of society, that nature should be without human intervention, because it is here that the mind and body achieve the most freedom. The world he escapes is not necessarily one of territorial imperialist boundaries; however, with the introduction of ‘neo’-colonialism, a psychological coloniality emerges that centres classification and ordering as a means of control and superiority (Esposti, 2024), which Chris struggles with after destroying his forms of ID and communication. Furthermore, the origin of Chris’ journey is informed by neocolonial identity models, which he sought to escape (Spivak, 1991) – away from a culture and state that planned his whole life out for him and monitors it as such through work and financial contribution.

The film’s critique of neocolonial gazes on nature as well as the internal oppression felt by Chris is clear but dynamic. His journey to his perceived freedom in the ‘wilderness’ is interrupted time and again by neocolonial avenues both internal and external, but these fail to halt his journey. He arrives in Alaska, excited and existentially inclined as to his life’s purpose and willing to discover his own identity without neocolonial, capitalist structures influencing this; a kind of reformation and resolution to fight against these systems (Sartre, 1964). By questioning these dominant narratives, the audience understands more effectively the emotional drive behind Chris’s desires, eliciting sympathy and relatability in his need for a different kind of existence.

“Look Mr. Franz. I think careers are a twentieth century invention and I don’t want one. You don’t need to worry about me. I have a college education. I’m not destitute. I’m living like this by choice.” – (Into the Wild, 2007)

The Power of Subjective Engagement

Geography has long been concerned with the visual in helping us understand spatial and place-based knowledge (Jacobs, 2024). Doreen Massey championed film’s involvement within geography in critiquing and reordering our global imaginations to construct social relations and identities (Lury and Massey, 1999). However, Lury warned of film as “a refuge, as contrast, as education or seduction” (1999, 232). By understanding the romanticism and potential warped realities of visual art, “Into the Wild” starkly contrasts its beautified cinematography in the final moments of Chris’s life. The sadness and grief at realising that the film does not end happily but with a few shuddering breaths and a quote by a man starving to death in the back of an old Fairbanks City bus, does somewhat distort the rose-coloured lens that incentivises the audience to want to pursue Chris’s lifestyle. I believe that this visceral framing, in contrast to the beautification of a vagabond life, is why this film stands as a potent example of the true pursuit of happiness despite the capitalist, neocolonialisms that may persist.

Emotional resonances such as this are why subjectivity within film should help communicate geographical ideas to a wider audience. While traditional human geography prioritises objectivity when competing with scientific paradigms, what it wants is a lack of personal bias. Hoefle (2022) proposed a model to utilise subjectivity where the audience should be able to step into the researcher’s shoes, emphasising that a shared relational narrative can help eliminate bias without sacrificing the personal lens. It is models such as these that support the need for film as a means of communicating complex geographical ideas, that subjectivity need not be devalued as traditional geography might have, but instead embraces the lived experiences of those with stories to tell of the world, as Chris did.

Towards a Subjective Turn

By tying geography with visual art, “Into the Wild” teaches us to worry less about the validity of emotional and subjective resonances and instead how these narratives can educate and influence a wider audience. Associating art and geography naturally encourages an ‘expanded field’ perspective (Hawkins, 2013) away from entrenched academic practices, which is precisely what is needed in the current social, political and cultural scope to better understand our world and the systems of oppression that may seek to undermine our creative and academic curiosities.

Chris McCandless’ parting message to the world was simple.

“Happiness is only real when shared.”

The need to escape and never have to worry about money, value, or identity in a materialistic, overstimulating, extreme world has never been more desired. But it’s stories like Chris’s that force you to stop and think about the implications, that happiness is the ultimate goal, not escape, and that happiness is only real when you share it with others who resonate with your ideals. Emotional resonance is just that, it resonates in ways we have yet to quantify.

But there is beauty in that, too.

There is pleasure in the pathless woods.

Reference list

Driver, F. (2003) ‘On Geography as a Visual Discipline’, Antipode, 35(2), pp. 227–231. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00319.

Esposti, N.D. (2024) ‘What Happened to Neocolonialism? The Rise and Fall of a Critical Concept’, Journal of Political Ideologies, pp. 1–21. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2024.2346193.

Filmgrab (2021) ‘Into the Wild’, Filmgrab, 30 April. Available at: https://film-grab.com/2010/07/14/into-the-wild/ [Accessed 18 Apr. 2025].

Hawkins, H. (2013) For Creative Geographies: Geography, Visual Arts and the Making of Worlds. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Hoefle, S.W. (2022) ‘Objectivities and Subjectivities in Geographical Research: A Philosophical Inquiry into Methods’, Treballs de la Societat Catalana De Geografia, 93, pp. 53–84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2436/20.3002.01.219.

IMDB (2007a) Emile Hirsch in ‘Into the Wild’. Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0758758/mediaviewer/rm2950056193/?ref_=ttmi_mi_69 (Accessed: 17 April 2025).

IMDB (2007b) Emile Hirsch in Into the Wild (2007). Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0758758/mediaviewer/rm3850732544/?ref_=ttmi_mi_2 (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

IMDB (2007c) Hal Holbrook and Emile Hirsch in ‘Into the Wild’. Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0758758/mediaviewer/rm2747891968/?ref_=ttmi_mi_9 (Accessed: 14 April 2025).

Into the Wild. (2007) Directed by Sean Penn. [Feature Film]. United States: Paramount Vantage.

Jacobs, J. (2024) ‘Making Space for Film with Film Geographies’, Academic Quarter: Akademisk kvarter, 27, pp. 96–112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.54337/academicquarter.i27.8830.

Katz, C. (2002) ‘Vagabond Capitalism and the Necessity of Social Reproduction’, Antipode, 33(4), pp. 709–728. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00207.

Lury, K. and Massey, D. (1999) ‘Making Connections’, Screen, 40(3), pp. 229–238. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/40.3.229.

Oyenuga, O.G., Adebiyi, S.O., Dakare, O. and Omoera, C.I. (2019) ‘Knowledge Sharing Limitations among Academia: Analytic Network Process Approach’, Management of Organizations: Systematic Research, 81(1), pp. 39–54. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/mosr-2019-0003.

Rogers, E. (2012) Critical Artistic Response to Environmental Neocolonialism Embedded in Wildlife Conservation. Masters Thesis. University of Buffalo. Available at: 10.13140/RG.2.1.4282.4566.

Santos, M. (2021) For A New Geography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sartre, J.-P. (1964) Colonialism and Neocolonialism. London; New York: Routledge.

Spivak, G.C. (1991) ‘Neocolonialism and the Secret Agent of Knowledge’, Oxford Literary Review, 13(1), pp. 220–251. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3366/olr.1991.010.