“Travel is about the gorgeous feeling of teetering in the unknown.”

– Anthony Bourdain

There are few greater small pleasures in life than taking the train through a new country.

In this case, I was nearing the end of a month-long Interrail trip with a group of friends in one of my summers out from University. For our transport, we had taken the night train from Bratislava to Rijeka after a glorious few days exploring the Tatra mountains on the Slovakian-Polish border.

Sleeping on a night train feels like sleeping and waking in a world where neither time nor reality exists. At the same time, the discomfort of a small bunk for anyone over 150cm tall, the cramped shared bathrooms per train car or the loud snoring of a nearby bunk mate can be a rude awakening, both literally and metaphorically.

Due to a late booking on our part, and since there were 8 of us travelling together, we ended up in different compartments entirely. So as the night train rolled onto the deserted platform of Bratislava’s main station, we waved goodbye to each other until the morning.

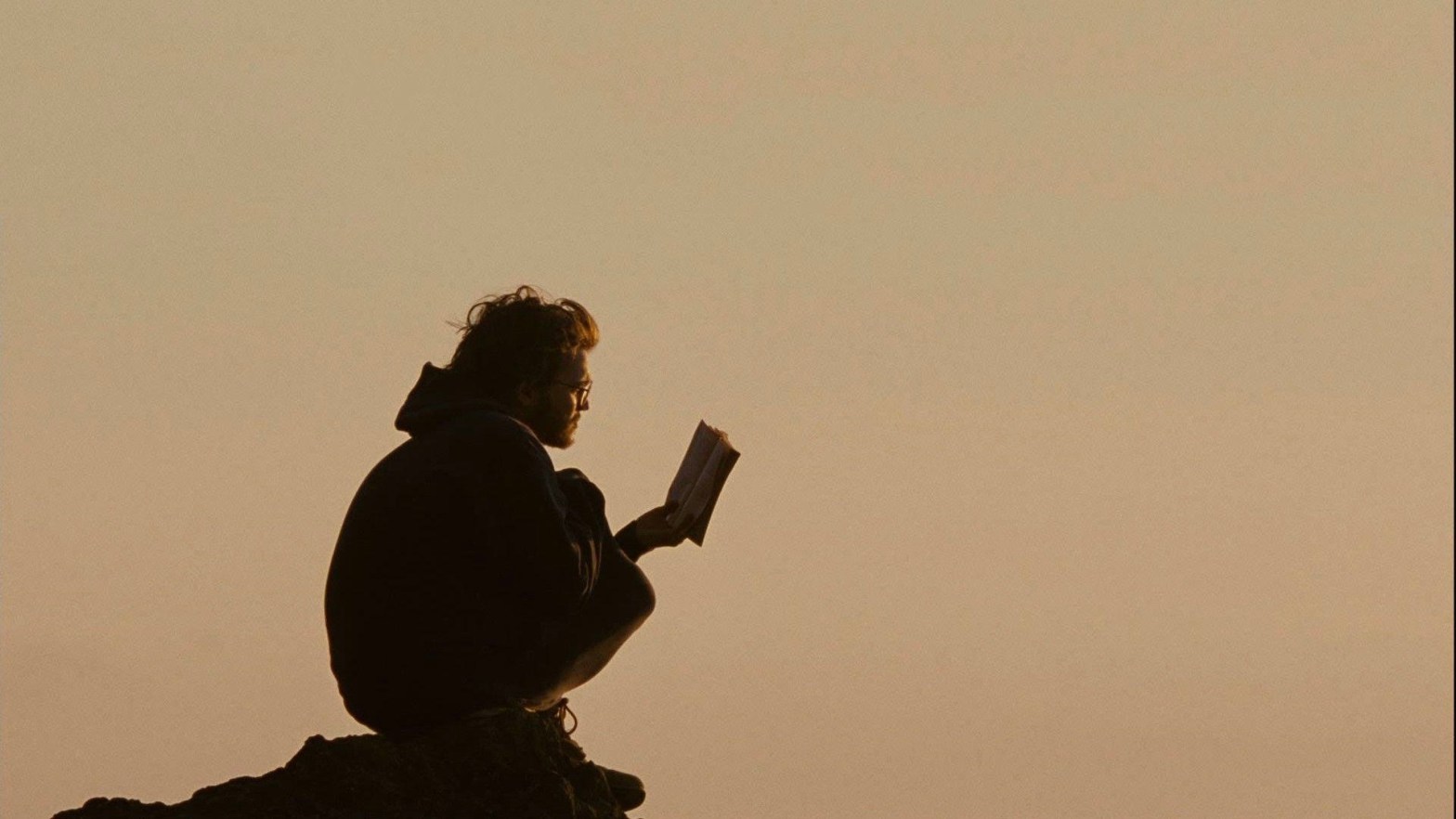

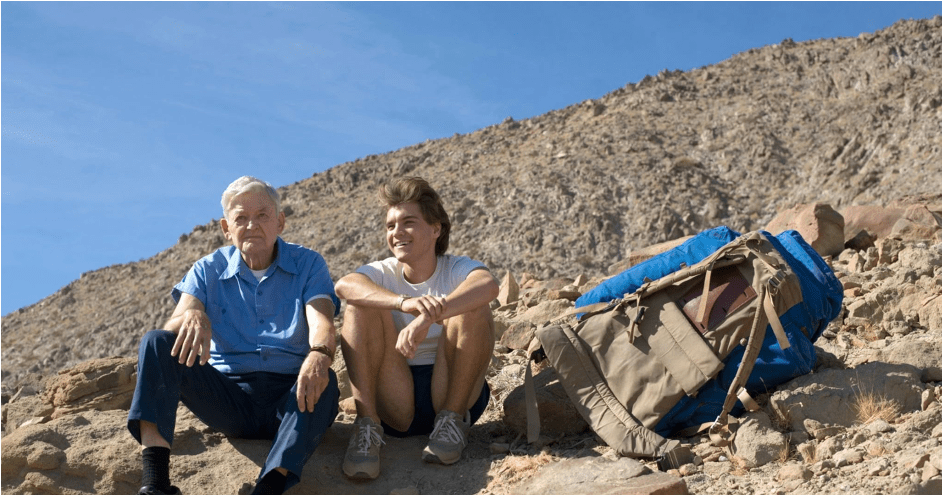

After lugging my large backpack that I’d been living out of for 3 1/2 weeks so far, back onto my back, I found my compartment. My fellow compartment-ees were an elderly Slovakian couple that I quickly learned spoke no English, but were incredibly friendly and smiled at me as I entered. With a little help from the older man, I managed to squeeze my backpack onto the top luggage rack and then spent the next 10 minutes fiddling with the locking mechanism to bring my bunk bed down and put on my sheets so I could get ready to sleep.

After washing my face and brushing my teeth in the cramped train toilet at the end of the car, I settled in for the night, watching the Hungarian landscape fly by in the night. This peace didn’t last very long.

Being awoken at 3am by some brutal passport checks and torches being waved in my face was not quite how I’d envisioned my night going, but after a lengthy double check by Croatian border officials and the fear of being arrested truly drilled into each of us, we slowly pulled away from the platform and continued on.

Watching the night and lights of civilisation flying past was so exciting; you could even see the stars. My bunk was comfy, and I slept quite well after that, luckily with no snoring neighbours in the cabin.

Around 7 am, I woke up since the Slovakian couple were already folding away their beds and had left me my share of the breakfast rations – a packaged croissant and an apple. The kind man also left the cabin to let me change in private, and soon enough, I met up with my friends to brush our teeth and lean out of the train’s open windows. It was a true pinch-me moment, feeling the warm wind from the Adriatic on our faces and watching as the coastline snaked to meet the train tracks, with smaller sand-coloured houses emerging from green hedges dotting the hillside.

After packing up the remnants of my belongings and saying goodbye to my friendly cabin-mates, we trundled slowly into Rijeka’s main station. Despite the sunny yellow of the train exterior and the bright blue sky, thunder rumbled in the distance, so we resolved to get to our hostel as soon as possible.

As we passed each street corner, among blocks of sandstone flats, whiter modern new-builds and old shop fronts with large hanging signs advertising cafes and barbers, we dodged the torrential downpour that soon followed the ominous clouds and ducked from doorways to cafe awnings to underpasses. It soon became clear that the rain wasn’t going to let us stay dry, so the remaining uphill walk to our small hostel was spent in silence, interrupted only by the patter of rain on the concrete steps.

The hostel was a tall but thin building on a hill with a stunning view of the sea that was partially obscured by a large willow tree hanging across the front facade. The beds were comfy if a little difficult to climb into, especially if given the top bunk, but the room was big enough for us all to unpack, and before long, the room more closely resembled a dry cleaners with all the wet clothes hanging between the beds on makeshift elastic washing lines and shoelaces.

As soon as the rain stopped, though, we collectively gathered our sleep-deprived selves, armed with half-damp towels and crumpled tote bags, and headed towards the only source of food we had found so far, Aldi. The streets were starting to steam from the evaporating rain, and the sun began to shine through the leafy canopy that shielded the residential streets higher up. The steps only continued as we made our way, finally to the main destination of the trip so far, the ocean. With the sun now fully shining, I thanked my sleepy brain for at least remembering sun-cream and we descended through a small opening at the cliff edge where a steep and uneven staircase was built into the rock towards the water below.

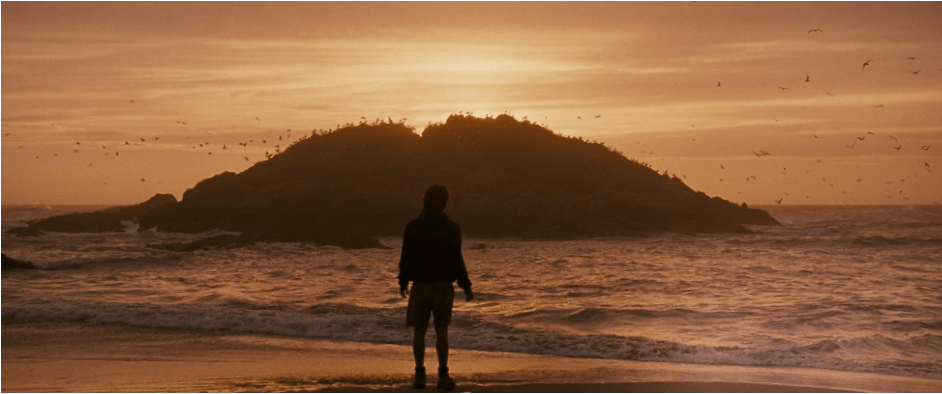

Now I have seen my fair share of blue water in my life but little compared to the green and blue waves I witnessed at the cove we found outside Rijeka’s city centre. It was all the colours found in the blue and green spectrum mottled only slightly by the dark outlines of rocks below the surface that were so clear they appeared so close yet remained far below the surface.

The baguettes, tomatoes and pesto were forgotten in our bags. We quickly changed and ran straight in, submerging in the temperate water with a slightly colder layer on the surface after the recent rain. It was the most amazing feeling after our disturbed sleep on the train, and soon enough, we were diving to find rocks and daring each other to jump off the cliffside when a path was precariously discovered.

That night, we dined in town in a small restaurant with chairs spilling out into the main square. The streets were quiet but warm, and the food fresh and hearty. The locals welcomed us with an indifference that was both an insult and a compliment all at once, and soon enough, we walked the long way home, past the fishing boats bobbing in the green waves and the marina lights guiding the way.

From my hostel bed, I could look out past the chipped wooden shutters towards the ocean and the lights on the other side of the bay and feel content in a way I hadn’t in a long time.

It’s not wrong to want to get away sometimes because living life one way can become exhausting. Finding a new perspective can give you the clarity you need, or sometimes just swimming in clear blue-green water can do the same. Either way, I recommend it, and even better if you can travel there by train.

It helps to build appreciation for the journey because you see all the parts between the starting point and the destination. Or at least the kindness of strangers saving you an apple or brushing your teeth out the window with a view of the Adriatic.

There aren’t many transport options that can guarantee that.